A psychology geek’s take on creativity and how it relates to flow states

Download Flow Lab

Flow Lab is your AI-powered mental fitness app that helps you experience the highly productive Flow State more often. So get your 7-day free trial and it and train your mind with science-backed guided and personalized meditations: ![]()

![]()

This article was written by Flow Lab’s Head of Content and MSc. psychologist Eva Siem. She studied at the University of Groningen (NL) and is specialized in the area of performance and motivational psychology. In her articles, she combines findings from psychological research with practical tips from her experience as mental fitness coach and workshop trainer.

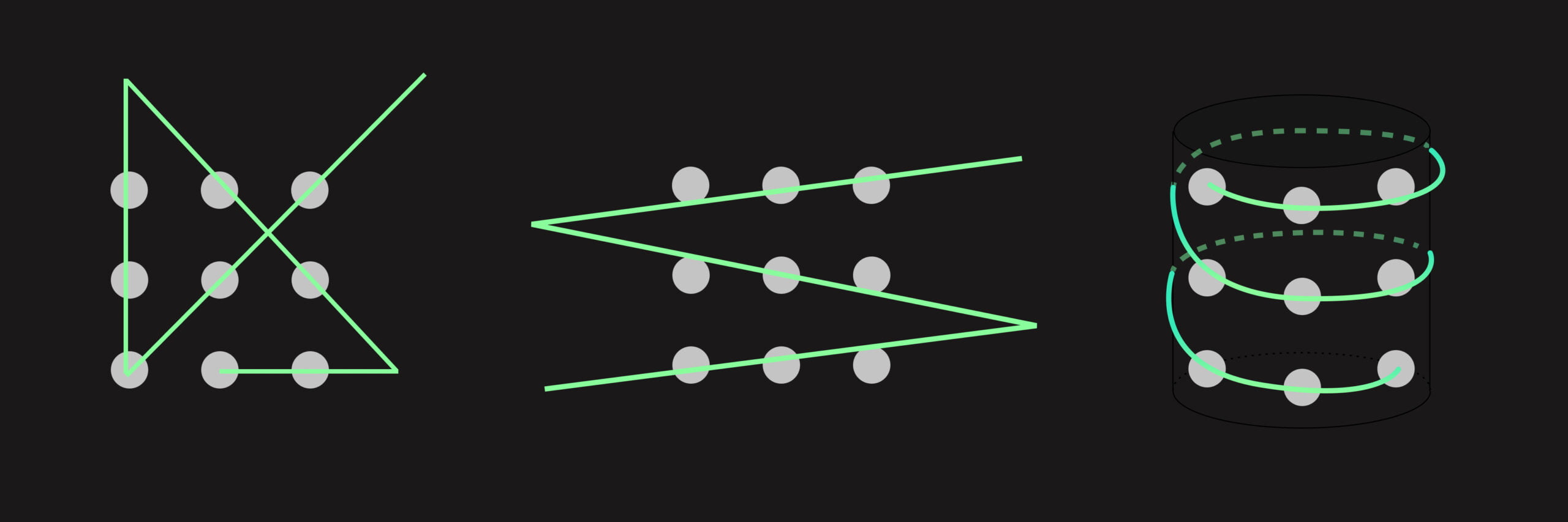

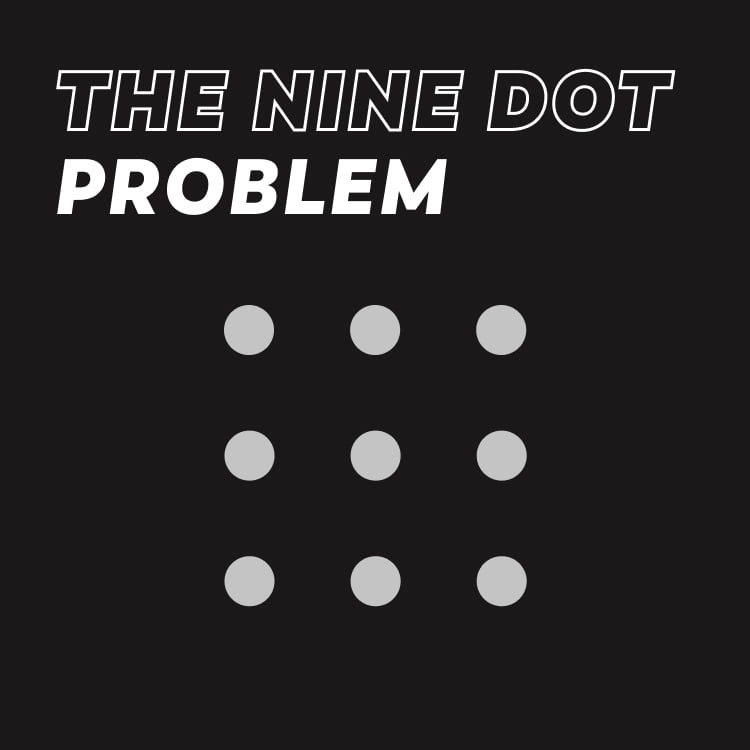

Before we dive deep into the psychology of creativity and flow, let’s start with the “Nine Dot Problem”: You may have stumbled across this puzzle before. If not, now is your chance to test your ability to think outside the box. Connect these 9 dots with no more than 4 lines. Without lifting the pen from the paper. That’s the rule. How many ideas can you come up with to solve this task?

If that’s too easy for you, how about 3 lines? (Using Google is cheating!)

This is a classic puzzle to assess creativity – a cognitive skill that becomes increasingly valuable. As humans, we have the unique capacity to imagine things that don’t exist (yet). Any form of innovation – airplanes, cell phones, art, the shirt you’re wearing today, … you name it – once originated as an idea in the human brain.

With most of the information being only one click away in these digital times, being able to combine existing knowledge in new ways may become increasingly important. An IBM survey (2010) – with 1500 face-to-face interviews – revealed that creativity is the most desirable skill in CEOs from all over the world. But hold on, is it a special attribute only few brilliant minds are equipped with? What is creativity in the first place? And how can we train it?

Stay tuned for the state of the art: The psychology behind this magical skill, how it relates to flow states and what you can do to level up your creativity!

What is creativity?

While there are different answers to this question, a growing number of researchers thinks of creativity as the production of ideas, insights, or products that are novel, original, and useful in a given context (e.g., Sternberg & Lubart, 1999). Using a paper bag to protect yourself from rain may potentially be novel, but not very useful as the paper will quickly get soaked and tear. Using an umbrella is useful, but not novel at all and may be considered mundane. Yet, as De Dreu and Nijstrad (2017) remind us, “novelty and usefulness are social evaluations” (p.353). In other words, what may be considered creative in one context and time, may be regarded as boring or useless in another. Apart from that, there seems to be consensus that creativity is based on already existing knowledge, or in Koestler’s (1964) words: “We cannot create something from nothing” (p. 30).

What influences our creativity levels?

It may sometimes seem as if it is something only a few lucky ones were gifted with. But in fact, creativity is said to be inherent to human cognition – something we all have in us (e.g., Ward, Smith, & Finke, 1999). There are various factors influencing our level of creativity. To name a few: Experimental studies have shown that intrinsic motivation are conducive to creativity. When extrinsic motivation was experimentally induced, participants exhibited poorer problem solving skills (McCullers & Martin, 1971) and lower creativity levels (Amabile, 1979). Besides that, Tierney and Farmer (2002) found an increase in creativity when creative self-efficacy increased as well (i.e., the belief that you have the ability to successfully perform a creative task). Also your mood, how satisfied you are with your job, or other psychological states can have an impact on your creativity (Amabile, Barsade, Mueller, & Staw, 2005; George & Zhou, 2007).

There are many things that still need to be explored about this valuable skill, but one thing is certain: In our modern, fast-paced and competitive society, everything becomes increasingly complex and we’ll be confronted with new problems and uncertainty. So we might also need to come up with new solutions and get creative.

While it may sometimes seem as if it is something only a few lucky ones were gifted with, creativity is actually said to be inherent to human cognition - something we all have in us.

Do you need “more” or “better” for creativity?

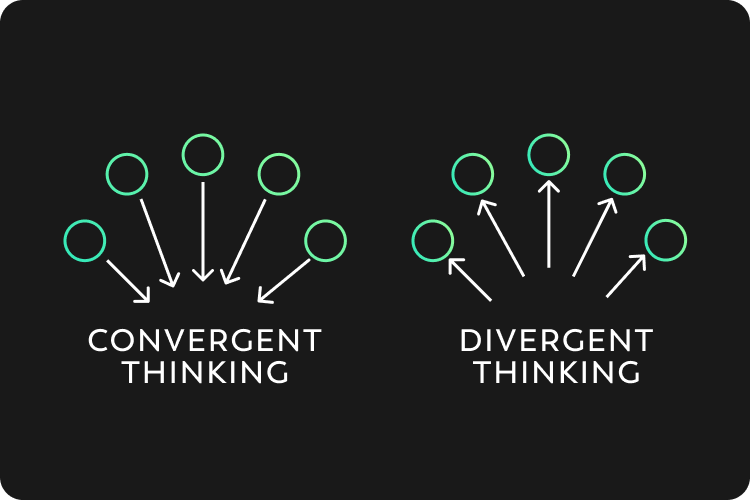

In the mid-20th century, Guilford (1950), former president of the American Psychological Association, conceptualized creativity based on two information processing modes: divergent and convergent thinking. Convergent thinking refers to finding and honing the single best solution to a problem. Sherlock Holmes, for instance, shows us how it works: bringing facts together from various sources and applying logic to find the best answer to a problem. Divergent thinking, in contrast, is employed when confronted with an open-ended question and refers to creating a great number of varied solutions (by the way, you were facing a divergent thinking task in the beginning). Another popular divergent thinking test is the “Alternative Uses Task”. Here you need to come up with as many alternative uses for an object (e.g., a cup) as possible. The ideas will then be evaluated with four indicators: fluency (your total number of ideas), flexibility (the number of categories your ideas can be assigned to), elaboration (how much detail you provided and how well the ideas can be organized) and originality (how unique your ideas are). The distinction between these two processing modes is the basis for a lot of research that has followed ever since.

The Dual Pathway to Creativity Model

And while there are as many models on creativity today as you can imagine when thinking divergently (better don’t tell this joke at a party…), the Dual Pathway to Creativity Model (DPCM; Nijstrad, De Dreu, Rietzschel, & Baas, 2010) summarizes different lines from over 40 years of research. Among other things, the researchers distinguish between a cognitive flexibility and a cognitive persistence route. The former is the classical “out of the box”-thinking needed to switch to another perspective or approach (thereby dominant in divergent thinking). It involves low cognitive control and a certain amount of randomness, ideally leading to sudden insights or ideas. When thinking about creativity, most people forget about the latter one – cognitive persistence. It requires sustained focus during the systematic search for the final solution (thereby dominant in convergent thinking). That means, when talking about creativity, we need to distinguish which kind of task we are confronted with and what helps us to solve it – cognitive flexibility or persistence. And we’ll get to that – but before that, we can zoom into the brain to unveil what we know about the neurobiological mechanisms so far.

The neuroscience of creativity

… on a neurochemical level

Both cognitive persistence and flexibility seem to be modulated by dopamine release in the brain. More specifically, persistence is fueled by dopamine innervating the prefrontal cortex (Goldman-Rakic, 1992) which is the area directly behind your forehead. During cognitive flexibility thinking processes, the dopamine pathways in the striatum (a primary structure of the basal ganglia which is part of your forebrain) seem to be involved. Apparently, the relationship between dopamine in these structures and creative performance follow an inverted U-shaped function: With increasing dopamine levels, performance improves as well, up to a certain point where too much dopamine correlates with a drop in performance (e.g., Akbari Chermahini and Hommel, 2010, 2012b; Boot et al., 2017a,b).

… on a neuroanatomical level

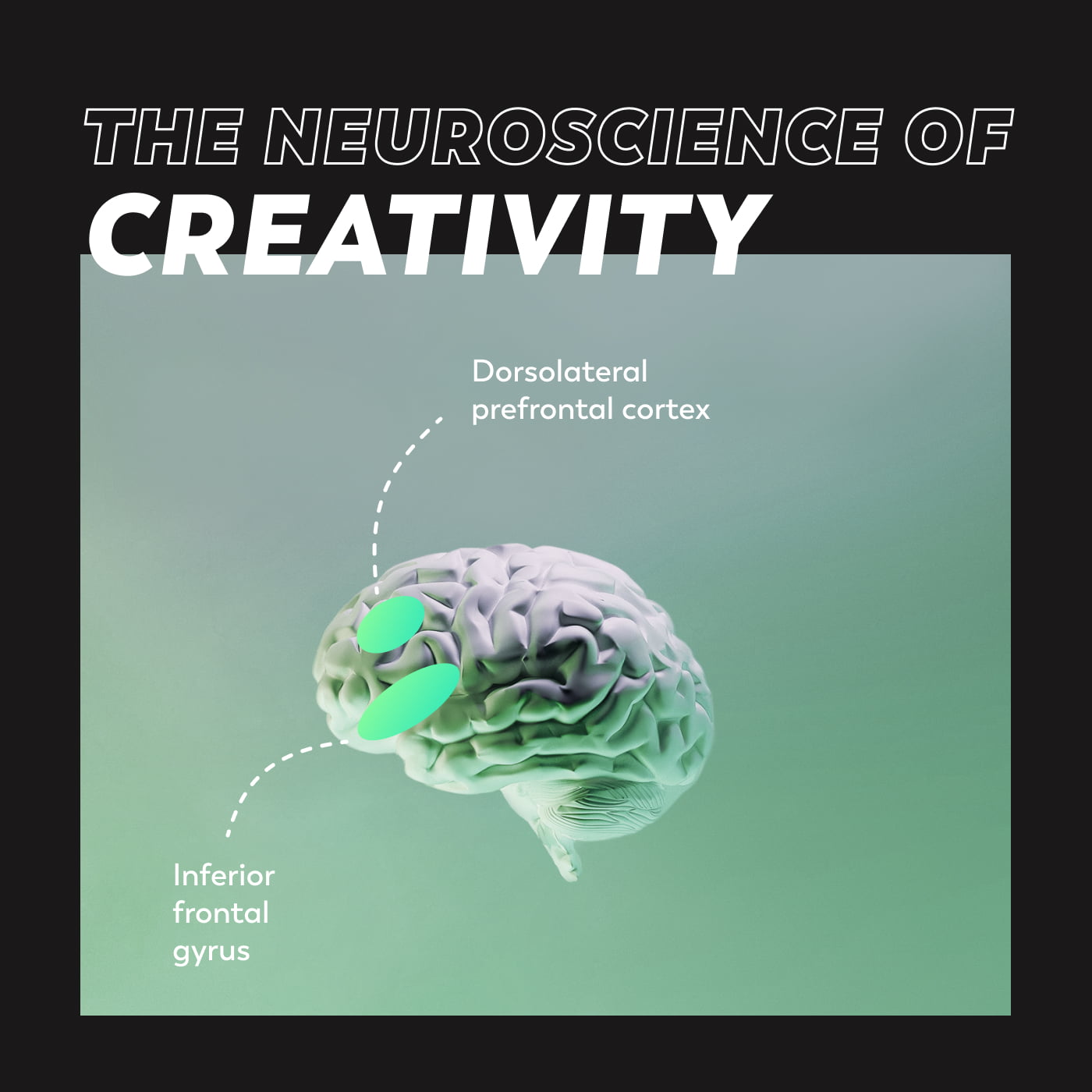

For certain neurobiological mechanisms underlying creativity, researchers are still tapping in the dark. But there are still a few reliable patterns:

Apparently, there is a greater functional connectivity between brain areas associated with cognitive control and random, spontaneous thought processes. For those who are waiting for the geek knowledge:

During divergent thinking tasks, the left inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) is more activated. This structure is responsible for, for instance, cognitive control, idea generation and selecting a response to a certain stimulus (Abraham et al., 2012; Benedek et al., 2014; Chrysikou, 2019). At the same time, regions of the so-called “Default Mode Network” (DMN) are more active as well. This network includes different brain regions such as the medial prefrontal cortex, the posterior cingulate cortex, the adjacent precuneus, and bilateral inferior parietal lobes (Fox et al., 2005; Gusnard & Raichle, 2001). It is responsible for a wide range of imaginative processes such as mind-wandering or simulating a certain situation (Andrews-Hanna, 2012; Christoff et al., 2009; Hassabis & Maguire, 2007). (Fun Fact: The DMN not only correlates with spontaneous and imaginative thought, it was itself a serendipitous discovery; Buckner, 2012).

During creative processes, spontaneous thoughts help to come up with new ideas and associations, while controlled thinking helps to filter irrelevant information and shift the focus back to helpful ideas.

Recent research has found a greater connection between the IFG and the DMN. This indicates that both controlled and spontaneous thought processes are involved in creativity. One explanation may be that creative thinking involves consecutive processes. Spontaneous thoughts help to come up with new ideas and associations. Afterwards, controlled thinking helps to filter irrelevant information and shift the focus back to helpful ideas.

During convergent thinking tasks, the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) – a region involved in cognitive control and working memory – enhances creative performance: It increases task focus and inhibits any information that is irrelevant to the task (Beaty & Schacter, 2018). This way, we can filter any information and ideas while simultaneously maintaining our focus to find the best solution to our problem.

The relationship between creativity and flow

The relationship between Flow and creativity is an interesting one. Because the groundwork for Flow theory was actually done when Flow father Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi studied creativity. He observed creative artists who worked feverishly on their tasks. But, once finished, they dropped it and never thought of them again. And while external rewards such as fame or money didn’t seem important to them, Csikszentmihalyi wondered what actually drove these artists. This eventually led to the discovery of the flow state. Although flow and creativity seem to be closely intertwined, there are a few conceptual issues making their relationship less clear:

Cseh (2016) explains that automaticity is a central component of Flow and arises for well-practiced activities or with a certain level of expertise. Creative work, however, is too ambiguous and complex to become automated. And require novel ideas as well as assessment of their quality. Likewise, the prerequisites of feedback and clear goals may not be fulfilled in this context: Since creativity is subjective and dependent on the social context, how can artists know whether their ideas are sufficient and innovative or not? This is where researchers dissent: Csikszentmihalyi argued that there is some kind of self-feedback involved that is learned through experience. Simonton (2000), in contrast, thinks that this kind of predictive expertise is not learnable in the creative realm.

Flow enhances creativity

But no matter how exactly they are conceptualized or related, there is quite some evidence that Flow enhances creativity: Yan et al. (2013), for instance, found that knowledge sharing among employees facilitated Flow. And this, in turn, increased creativity. Likewise, Zubair and Kamal (2015) showed that Flow correlated with workers’ creativity. And Byrne, MacDonald and Carlton (2003) linked Flow with more creative musical compositions.

How to increase creativity and flow…

Alright then, what can you do to increase creativity? Here is a collection of science-based tips:

Tip #1: Become curious

Creativity is a mental skill. That’s why training your mind is also the first tip. Particularly, becoming curious is a key to both creativity and finding Flow. Schutte and Malouff (2019), for instance, found that a curious mind facilitated Flow. And this, in turn, boosted creativity. This could mean approaching your current tasks with a different mindset and repeatedly asking yourself what else there is to learn for you. Or you could become curious by asking more questions, by being more attentive in any conversation or by proactively learning something new – which brings us to Tip #2.

Curiosity is a key to both creativity and Flow states. Click To Tweet

Tip #2: Broaden your horizon

We already learned that creativity arises from an existing knowledge base. But this is something we first need to build. That’s why you can begin by establishing a routine where you learn something new, perhaps even from a completely different field. This could be a new activity, reading about a new topic or talking to experts from another field. This also helps you to challenge your existing knowledge and prevent running on autopilot by relying solely on familiar thinking patterns. Read 5 pages per day about something outside your field. Or listen to a podcast episode a day on a topic that is completely new to you. All these things are a fantastic start!

Tip #3: Play and experiment

This one allows you to become a child again. That’s because play fosters creativity: In theory, it has already been shown that creativity correlates with playfulness (e.g., Barnett, 2007). In practice, we see that creative geniuses use experimentation as well. Did you know, for example, that Van Gogh was kicked out of his art class in a Parisian atelier? Apparently, “his drawings had nothing remarkable about them” (Smith & Naifeh, 2011, p. 514). Although he always had to hear that he was no good at drawing, Van Gogh started experimenting – from copying and sketching, over different media and also different philosophies he approached his art with until he finally found his style of vibrant colors and bold forms that he is now famous for.

So think about the tasks you’re usually working on. How you can experiment with your approaches or resources and adopt a more playful attitude? No need to be afraid of imperfection.

That’s a fantastic start. But as you know by now, different tasks may require different kinds of creativity. So we have gathered a bunch of other science-backed tips for you to level up your creativity. We first cover general creativity tips, before specifying for both divergent and convergent thinking tasks! And if you’re in a leading position, there are two extra creativity tips for organizations.

… for divergent creative thinking

Tip #1: Boost your mood

Yes, that’s right. Productivity is allowed to be fun. In fact, there is a ton of research emphasizing that a positive mood facilitates creative thinking (e.g., Baas et al., 2008; Akbari et al., 2012). For example, the Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions (Fredrickson, 2001) explains that positive emotions broaden our “momentary thought-action repertoire”. In other words, we broaden our focus and become more explorative – just what we need to be creative. Other studies on the heart rate variability found that positive emotions resulted in a more coherent pattern of the heart’s rhythm (McCraty et al., 2006; Tomasino, 2007). The researchers assume this to be the basis for creativity, innovation and even more Flow. Also, the anterior cingulate cortex seems to be conducive and active right before spontaneous creative insights (“aha” or so-called “Eureka” moments). And it gets activated by what? Yep, good mood (Subramaniam et al., 2008).

So perhaps you can negotiate with your boss to turn up your favorite Happy-Playlist in the office when working on creative tasks – research is on your side (Ritter & Ferguson, 2017). Alternatively, you can go for our mood-boosting Flow Sessions such as “Thank Me Later” to appreciate all the things you can be grateful for or “Mountain Top” to acknowledge your accomplishments and increase your self-efficacy beliefs.

Good mood facilitates creative thinking and increases the likelihood for creative insights (“Eureka” moments). Click To Tweet

Tip #2: Your mind is allowed to wander, finally!

When it comes to productivity, a wandering mind is deemed debilitating in most cases. Creativity research, however, reveals the benefits of defocused attention. Apparently, an open, wandering mind aids in generating new and more far-fetched ideas (e.g., Eysenck, 1993, 1995; Guilford, 1967; Mednick, 1962; Simonton, 1999, 2003).

So whenever your concentration drops or you’re stuck in a rut, you may plan a session of intentional mind-wandering. Set a timer. Then let your mind roam freely around your question or problem. If you like, you can end that session with a reflection phase in which you write down and evaluate your ideas. Chris Bailey proposes a similar strategy in his book “Hyperfocus”: He recommends to consciously let the mind wander around a certain question while engaging in routine activities (e.g., doing your household chores). Bailey explains that “habitual tasks have been shown to yield the greatest number of creative insight” (p. 148) and encourage your mind to continue wandering until the task is finished, thereby serving as some sort of “anchor”.

Feel free to train purposeful and productive mind-wandering with our Flow Session “Intentionally Left Blank” in the training area of Focus.

Tip #3: The art of incomple

This one is on Ernest Hemingway who stopped his writing sessions in the midst of a sentence. Along similar lines, bestselling author and founder of the Flow Research Collective Steven Kotler wrote in his book “The Art of Impossible”: “By quitting when you’re excited, you’re carrying momentum into the next day’s work session”.

What’s behind this approach is the “Zeigarnik Effect” which shows that unfinished work sticks to the mind. Psychologist Bljuma Zeigarnik (1927) gave 164 participants different creative tasks such as kneading an animal, drawing a flower, crocheting or the like. While participants were allowed to finish some tasks, they were interrupted in the middle of others. Afterwards they had to indicate which of the tasks they remembered. The result: unfinished tasks remained up to 90% better in the memory.

Alright, what does this have to do with creativity? Well, the brain is wired to close these open loops. Dopamine gets pumped into the system that motivates us to solve uncertain situations, to explore and to take risks. The brain thus generates new ideas – even if they haven’t reached conscious awareness yet. Sleeping over a problem and “consulting your pillow” gets a whole new meaning now. Alright boss, how about also finishing work earlier today – for the sake of creativity?

Tip #4: Open your awareness

But your mind doesn’t necessarily need to wander to become creative. You can also try an open awareness meditation: because this has been found to increase cognitive flexibility (Hommel & Colzato). Do it right now for just a second: Ask yourself – what stimuli do you notice? What can you see? What do you hear? And what sensations do you feel in your body right now? Integrate exercises like this one into your daily mental fitness routine to bring your creativity to the next level, for example, with “Horizons” in the Flow training area of Focus.

… for convergent creative thinking

Tip #1: Train your focus

For problems that have one best-fitting solution, a persistent focus is indispensable. Studies confirm that convergent thinking benefits from focused-attention meditation (e.g., Colzato et al., 2012). Find a focus point (e.g., a visual focus point in your environment or your breath) and hold your attention there for as long as possible. You may start with a few minutes a day. With more practice, gradually increase the amount over time. In the Focus training area, you’ll also find sessions to boost your focus such as “Push Up Routine” or “Deep Now”.

Tip #2: Grumpy, but creative: Use your negative emotions

Alright, so positive emotions broaden our focus and may support the generation of ideas. Negative activating moods such as anger or anxiety, in contrast, make individuals more creative because of higher cognitive persistence. Just to be clear: This doesn’t mean you should put yourself in a negative mood for the sake of creativity. But it may be a way to turn negative emotions you are feeling in a certain moment into something positive. Research revealed that people with negative activating moods showed enhanced persistence and spent longer time on their task (De Dreu et al., 2008).

So rather see this as some kind of emotion regulation tool to channel your energy towards your goal.

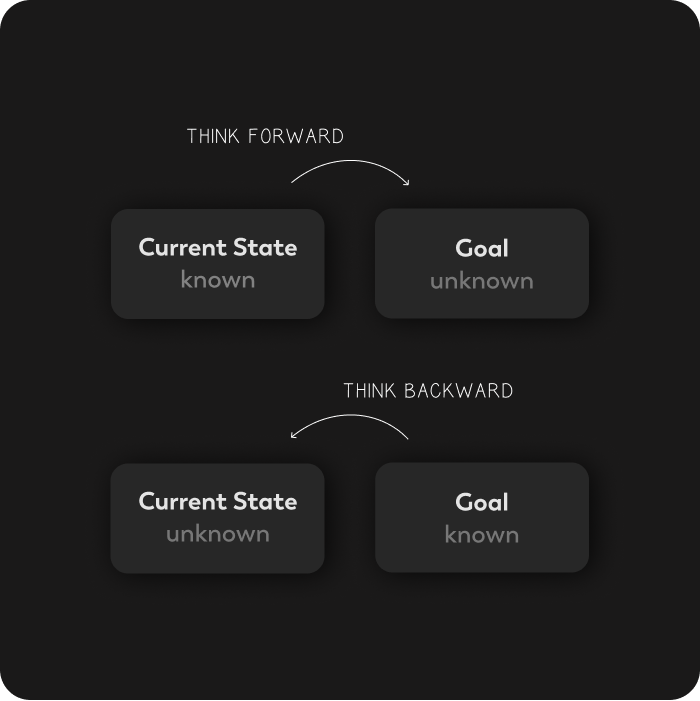

Tip #3: Think backward to move forward

New ideas may require new approaches. So rather than “thinking forward” toward a goal, try to “think backward” (e.g., Miller, 1959): Start with the goal in mind. From there, move backward by collecting information about the route that brought you there. A very simple example of this strategy that we’ve probably all applied at some point is to find out when you need to leave the house: Let’s say you need to be at work at 9 am for an important meeting. You usually need 35 minutes to get there. But when the bus gets crowded, it may also take 40 minutes. Perhaps you want to plan 5 minutes as a buffer – just in case. That means you need to leave at 08:15 am. This is how thinking backward works. You can apply this strategy for a wide range of other problems as well: for example, when visualizing your moves during a chess game, finding the best story you can tell when pitching your business idea, identifying the most appealing design for a website, determining the best User Experience for your app users, solving a mathematical problem – the list goes on. This process involves asking yourself questions like “What do I need in order to get there?” or “What needs to happen in order for XYZ to occur?”

Extra tips for creativity and flow in organizations

If you’re a manager and seek to enhance creativity among your employees, you may also try these tips:

Tip #1: Let your employees decide.

Research has shown that autonomy and flexibility increase creativity among workers (Macky et al., 2008) and support active job crafting (Mihelič & Aleksić, 2017). Perhaps you can let your employees choose certain tasks or assignments themselves or give them more freedom in how to approach them.

Tip #2: Create an atmosphere of togetherness

This one shouldn’t be underestimated for several reasons. The first one concerns psychological safety: feeling comfortable to speak up and share ideas, questions or thoughts without the fear of being judged for them. Especially when following unexpected, unexplored or unusual paths, feeling safe and supported by your team is the basis for productive work. Also, a supportive work environment may come with more knowledge sharing – without being anxious that someone could steal your ideas. And as we’ve learned earlier, knowledge sharing increases both Flow and creativity! Specifically, knowledge sharing correlates with increased focus and enjoyment. This, in turn, enhanced Flow and led creativity levels to spike.

I know, this was a lot to digest. Maybe go for one or two tips first and experiment what works best for you. In any case, becoming mentally flexible seems to be the basis for any kind of creative task. So train your mind to level up your creativity and best yourself. With regular practice, you’ll master both deep, focused work as well as open awareness and productive mind-wandering. Go ahead and check out our Flow Sessions in the training area of Focus!

Download Flow Lab now

And since we don’t want to be responsible for sleepless nights – here are a few solutions to the “9 dot problem” introduced in the beginning: