An answer to: “The Pursuit of ‘Flow’ Is Overrated”

Download Flow Lab

Flow Lab is your AI-powered mental fitness app that helps you experience the highly productive Flow State more often. So get your 7-day free trial and train your mind with science-backed guided and personalized meditations: ![]()

![]()

This article was written by Flow Lab’s Head of Content and MSc. psychologist Eva Siem. She studied at the University of Groningen (NL) and is specialized in the area of performance and motivational psychology. In her articles, she combines findings from psychological research with practical tips from her experience as mental fitness coach and workshop trainer.

We recently came across an article by Nir Eyal called “The Pursuit of ‘Flow’ is Overrated”. He assumes that flow is nice, but chasing it may be overrated because the guilt that might arise when not finding flow distracts us from our goals and makes things worse. Instead, one should foster “play” by adding constraints or becoming curious about a boring task.

Dear Nir, we agree with many of your points, but we have a few additional thoughts on this topic that we wanted to share. Because pursuing flow can be very valuable in our eyes. And here is why we think that:

We need a healthy path to high performance

It’s no news that workaholism and burnout still affect way too many people. According to Burnout Nation (2020), around 76% of US employees are currently showing symptoms of worker burnout.

There is no doubt that we need to lower that number. And in this context, flow is said to be a promising approach to high performance without compromising well-being (Peifer & Wolters, 2017). In this mental state of complete immersion in an optimally challenging task, productivity feels fun and effortless. And even better, it increases well-being (Csikszentmihalyi, 1999; Eisenberger et al., 2005; Kubovy, 1999), self-efficacy (Salanova et al., 2006), a sense of meaning (Delle Fave, 2009), creativity (Zubair & Kamal, 2015), work enjoyment (Maeran & Cangiano, 2013) and decreases the risk for burnout (Lavigne & Forest, 2012).

Flow is a promising approach to high performance without compromising well-being.

Is it possible to find flow in any task?

Sounds good, but is it really that easy? According to Eyal, it’s simply not possible to experience flow for every task for several reasons: He argues that, especially in the workplace, we may either lack the precondition of clear goals and/or immediate feedback and since we get paid for them, we don’t do our tasks for their own sake.

Interestingly, psychologists argue that the probability of finding flow is especially high at work (Csikszentmihalyi & LeFevre, 1989).

But not so fast. Let’s discuss these arguments one by one:

The autotelic nature of flow

Eyal: For one, the task at hand must be “autotelic” — that is, it must be done for its own reward. Doing something for the sake of getting rewarded (like completing tasks for a paycheck) is not autotelic. Well, that requirement pretty much rules out what people do for most of their working lives.

That’s an interesting one. It’s true that doing our work only because we get paid for it is extrinsically motivated. Yet the fact that we get paid for our job doesn’t mean that we cannot also be intrinsically motivated and enjoy our work.

The reason why Csikszentmihalyi called it “flow” instead of “autotelic experience” was that “in calling an experience ‘autotelic,’ we implicitly assume that it has no external goals or external rewards; such an assumption is not necessary for flow” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975, p. 36). That’s because an extrinsic goal can also become intrinsic during the process and still trigger flow (cf. Csikszentmihalyi 1975, p. 41ff).

The researchers Engeser and Schiepe-Tiska (2012) put it like this:

“[…] flow could be experienced in any activity, and not only in activities with a distinct “intrinsic” nature. In a working context, for example, an individual could be assigned to a task and become completely immersed in this activity while carrying it out. This would mean that an initially extrinsically motivated behavior could become intrinsic during its performance.” [emphasis added]

So it is possible to find flow at work, even though it’s not entirely “intrinsic”.

What if no one is giving me feedback?

Eyal: Flow-inducing tasks also require “clear goals and provide immediate feedback.” Again, that doesn’t translate well to hard work, for which getting immediate feedback is rare. Slaving away on a task that takes a long time to complete means feedback is inherently delayed.

The good news is: We don’t necessarily need other people to receive feedback. In fact, this prerequisite can also be covered by self-feedback.

Take creative tasks for example. Being creative requires novelty – inventing something that hasn’t existed before (Koestler, 1964; Sternberg & Lubart, 1999). Being able to assess whether one’s work is creative or not – without involving other people – seems rather counterintuitive at first, doesn’t it?

Csikszentmihalyi (who, by the way, discovered flow while initially researching creativity) argued that people can deal with this ambiguity of feedback by “internalizing the field’s criteria of judgment to the extent that they can give feedback to themselves, without having to wait to hear from experts” (1996; p. 116). And they do so by learning through experience and developing an intuition of what their audiences will like or dislike. This way, they get an instant and clear self-feedback to facilitate flow.

Apart from that, feedback can be inherent to the task. When writing a new book, for example, realizing how many paragraphs one has written during the past hour is also a form of feedback, isn’t it? That also implies that we don’t only receive feedback when our tasks are completed, but also during the process.

But what about the dark side of flow?

Eyal correctly states that productivity isn’t always fun:

Eyal: If there’s one thing I’ve learned writing my two best-selling books, Hooked and Indistractable, it’s that writing isn’t always fun. It’s hard work full of boredom, self-loathing, and self-doubt — pretty much the opposite of flow.

Totally, hard work is a pretty rocky road sometimes. And there are many emotional challenges attached to it. However, boredom or self-doubts shouldn’t discourage us because they are the opposite of flow. We think they should rather encourage us to learn how to regulate our emotions in order to find flow.

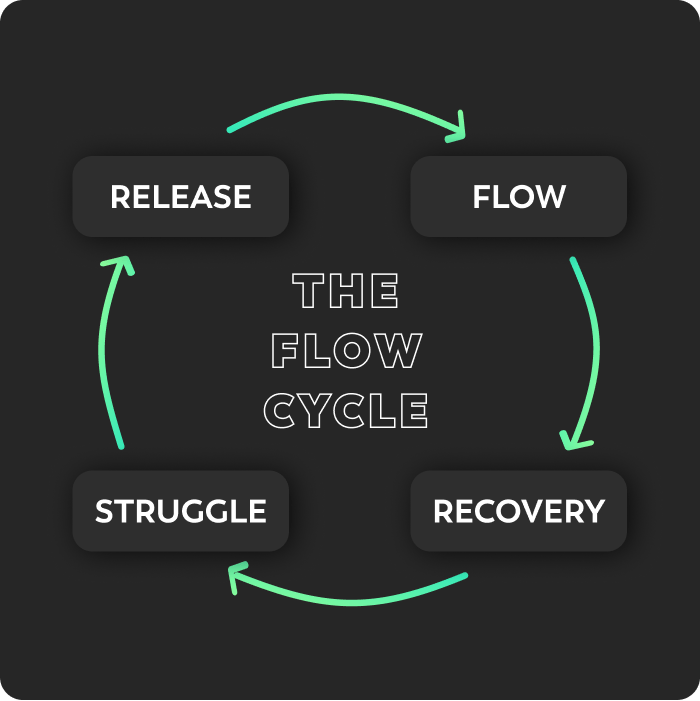

Don’t get us wrong – the goal is not to be in flow 100% of the time. That’s simply impossible. But by learning how to regulate our emotions, we make flow more likely. That’s because flow is a process: If you have heard of the “Flow Cycle” before, you know that finding flow usually begins with the so-called “Struggle Phase”. In this first phase, we feel overwhelmed, frustrated, and as if stuck in a rut. We’re collecting new information about the task and stress hormones are released. In order to move past this phase, we need to learn how to cope with these emotions, train persistence, acceptance and optimism. Because once we’ve overcome this hurdle (Struggle Phase) and taken our mind off the task for a moment (Release Phase), the third phase – the “Flow Phase” – can arise.

In order to cover these emotional challenges, our Flow training doesn’t only include focus exercises, but also interventions to tackle challenges such as fear of failure, boredom, self-criticism, perfectionism and stress.

Flow requires recovery

We’re on the same page regarding the statement that the dark side of flow shouldn’t be ignored. Flow can increase risk taking and, due to the release of a bunch of feel-good chemicals, it can also be addictive. Here, the last phase of the Flow Cycle comes into play: the “Recovery Phase”.

We give our mind and body time to replenish, consolidate what we’ve learned during the process and reproduce the neurotransmitters that help us find flow later again.

Active recovery strategies can, for example, include relaxation methods such as autogenic training, progressive muscle relaxation or relaxing breathing exercises.

Is “play” better than “flow”?

Eyal: There’s a way to stay focused on a task without waiting for the elusive state of flow. It’s called “play!”

Uh yes, we love “play”. It’s two birds, one stone: Play can make a task more interesting so we stay focused. And … it can also increase Flow!

Play and flow aren’t mutually exclusive. In fact, they go hand in hand.

In order to explain what we mean by that, let’s take a closer look at the ideas Eyal provides to integrate play into our work. He suggests to either “add constraints” or “find the mystery”:

Adding constraints

Eyal: Think of adding constraints like building a sandbox.

An unconstrained pile of sand spills in all directions. But contain that sand in four pieces of wood, and suddenly you have a sandbox where children will play for hours.

Similarly, when we let a task spill out into our day, we don’t see it as play, and we delay and procrastinate. But put a time constraint on the task, and watch yourself sprint to get it done.

The next time you have to respond to those dreaded emails or finish a blog post, you might give yourself only 20 minutes and see how much you can do. You don’t have to enjoy it or find a magical state of flow, but you will accomplish much more than you would if you had just let it languish on your to-do list.

Honestly, that’s a great idea. Especially when we’re bored, adding constraints can help to make a task more challenging. And it goes even further. Because this, in turn, helps us to find Flow as well.

In his book “Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience”, Csikszentmihalyi (2008) introduces Rico, an assembly line worker. In contrast to his colleagues who complained about the monotonous work, Rico found pleasure in his tasks by actively looking for new challenges. He actually applied what Eyal suggests: adding constraints. He aimed at optimizing his movements to reduce the time needed per item on the assembly line. As a result, he became the fastest worker in that company and frequently experienced flow states. No matter how often he already did the task, he approached it with an open and curious mind and thereby managed to transform boredom into flow (or avoid it in the first place).

So as stated above, it’s not one or the other, but play and flow can also go hand in hand.

It’s not one or the other. Play and flow can also go hand in hand.

Finding the mystery

Eyal: You might also infuse play into activities by looking for the mystery in something that other people don’t notice.

I found the play in writing my books by focusing on the unknowns surrounding the topic: I don’t write what I know, I write about what I want to know. The mystery around finding the answer propels me forward, whether I’m in flow or not.

Love it. Becoming curious is the best cure to boredom. And you may guess it already – curiosity also increases flow (Schutte & Malouff, 2019). Curiosity implies exploring something for its own sake (Kashdan et al., 2018; Litman, 2005). And as we’ve learned earlier, this intrinsic motivation plays an important role in experiencing flow.

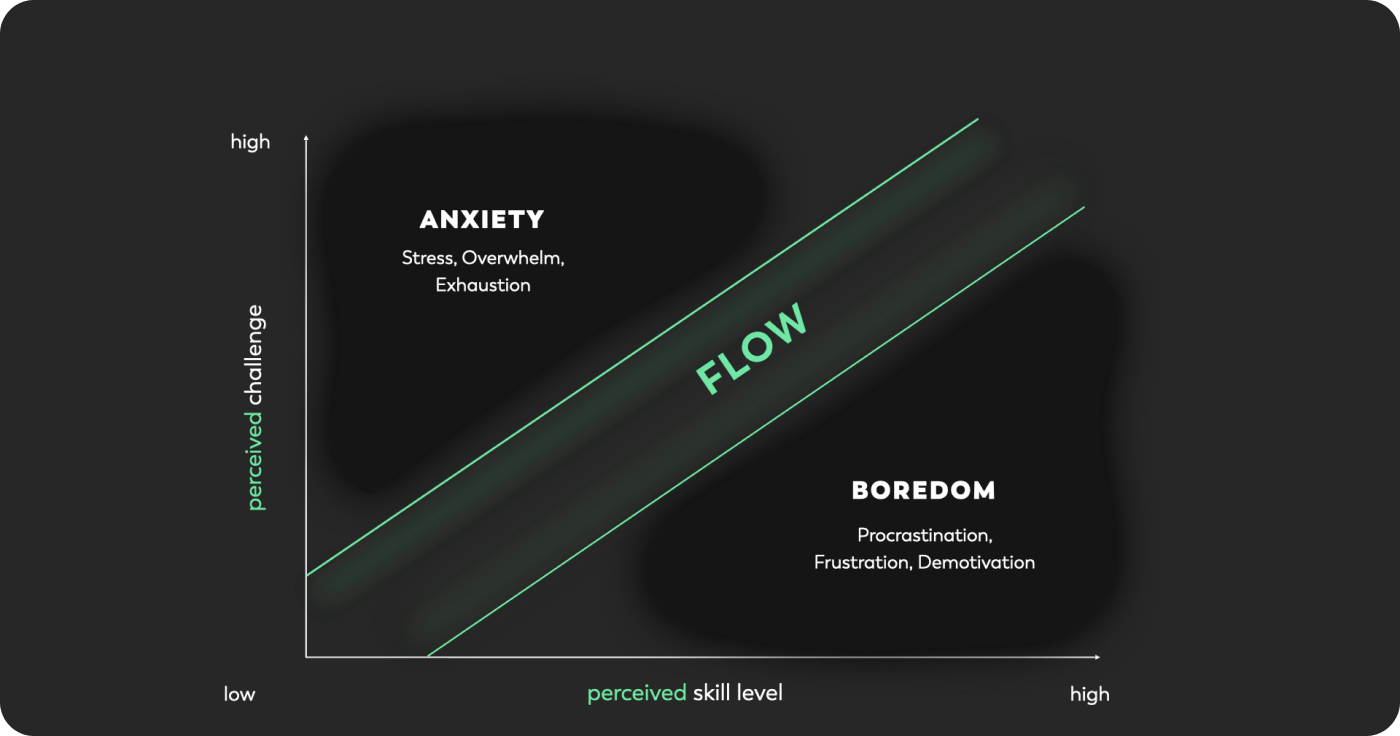

Perhaps you’ve stumbled across the “Flow Channel” already. It visualizes that we need to feel optimally challenged in order to find flow. If we think that a task is too difficult for us, we feel overwhelmed, anxious and stressed. If we think it’s too easy, we feel bored and demotivated.

The crucial point is that it’s about our perception of the task demands and skills. In other words, learning to look at a dreary task from a different perspective, reappraising it and actively looking for the things one can become curious about can make working on it more enjoyable and increase flow.

So the same thing applies here as well: Play is not necessarily an alternative to flow, it can actually make it more likely.

So what now?

We think that nobody should feel guilty about not finding flow! Yet we can maximize the likelihood of experiencing and sustaining flow and drawing from its positive effects. And this should go beyond muting the phone or sitting in front of a white wall. Instead, we need to improve our mental and emotional fitness. For us, this includes coping with frustration, self-doubts and all these emotional challenges that encounter us when at work.

We believe that mental fitness training can help us cope much more effectively with our everyday challenges and help us find more flow. And we believe that flow can make our everyday experiences much more enjoyable and our work more sustainable.

So – what do you think? Is flow overrated or something worth pursuing?