A psychology geek’s take on fear, anxiety and worry in the modern world and why it matters for flow states

Download Flow Lab

Flow Lab is your AI-powered mental fitness app that helps you experience the highly productive Flow State more often. So get your 7-day free trial and train your mind with science-backed guided and personalized meditations: ![]()

![]()

‘Tell me:

Which is the way I take;

Out of what door do I go,

Where and to whom?’

– ‘The Lost Son’, Theodore Roethke

Worry sounds like a small, sweet word. Something that we should be able to cope with easily. But it’s much easier said than done considering the speed of change in the modern world. Our worry has real ambition. We catastrophize things, imagine worst-case scenarios and ruminate over constant comparisons. It is petrifying which places our minds can wander and how anxious feelings worm their way into our confidence. “Am I really good enough? What will others think of me? What will happen, if I fail?” Even high achievers like Michael Phelps, Kristen Stewart and Adele are familiar with getting caught up in anxiety spirals. Apparently, negative thought patterns have very little to do with our actual abilities and accomplishments. To help you understand why fear and anxiety are so deeply rooted in us humans, we’ll take a dive into their underlying psychology. We will examine why our world and certain psychological variables trigger anxiety. And we will introduce scientifically proven techniques that will help you overcome anxiety-provoking thoughts while paving the way for more Flow. Stay tuned!

Fear, anxiety or both?

More often than not, fear and anxiety are used as equivalents. And it is indeed true that both states serve as an alerting signal to trigger an appropriate defensive behavior, i.e. the altering of body conditions to successfully cope with a threat or motivational conflict. However, in psychology there is no consistent conceptualization of fear and its connection to anxiety. Some clearly distinguish between fear (reaction to a definite, external threat) and anxiety (reaction to an unknown, imprecise threat) (Steimer, 2002). With this understanding, fear is merely understood as a more primitive emotion in response to an imminent physical danger. On the other side, some researchers think of anxiety as certain types of fears. Whereas fear can stem from both – an imagined or a real danger – anxiety only defines imagery stress (e.g., the possibility of being judged by others) (Öhman, 2000). In this context, scientists even suggest that anxiety can be interpreted as a “sophisticated” form of fear. Because at the core of anxiety lies a sense of uncertainty and uncontrollability. This provides an individual with the capacity to adapt and prepare for potential threats in the future (Engel & Schmale, 1972). Along these lines, Dr. Judson Brewer even suggests in his book “Unwinding Anxiety” that fear plus uncertainty equals anxiety. Besides that, worry can be understood as the cognitive component of anxiety, referring to the awareness of possible future dangers (Mathews, 1990). Nonetheless, it is rarely as useful as this definition might sound…

Scientists suggest that anxiety can be interpreted as a “sophisticated” form of fear, as at the core of anxiety lies a sense of uncertainty and uncontrollability, which provides an individual with the capacity to adapt and prepare for potential threats in the future.

Unraveling the neurobiology of fear, anxiety and worry

Although there remain different interpretations of the distinction between fear and anxiety, our minds and bodies still work the same way they did hundreds of years ago. Just like fear, anxiety and it’s cognitive companion worry serve as a response to a perception of danger. And anxious feelings are both psychological and physical. Our amygdala sends out an alarm to prepare our body for a defensive action. And our hypothalamus forwards the signal to set off a stress response. The sympathetic nervous system releases activating hormones like adrenaline and cortisol preparing the body to take action. Thus, our heart rate increases, our muscles tense, breathing quickens and we start sweating. Our prefrontal cortex, however, tries to put the nature of threat into context and to orchestrate an appropriate behavioral response. The problem is that, in an anxious brain, the amygdala overpowers the rational, analytical part of the prefrontal cortex with a stream of images and sensations. Therefore, we feel like our life is at stake, even though it’s all in our head.

Even though anxiety and worry are adaptive, preparing us for dangers through mental representations, excessive worry causes more problems than it resolves. Research suggests that worry often relates to personal and emotional threats to the self rather than actual problems in the real world (Mathews, 1990). Anxious individuals are also more likely to internalize threatening information and interpret ambiguous events as dangerous. And they tend to repeatedly rehearse intrusive and uncontrollable worries in their head without actually solving them. Besides that, Michael Eysenck (1985) discovered that anxious individuals are prone to having clusters of worry-related information in their long-term memory. Hence, they are more likely to recall threatening events, which usually results in unnecessary stress and an inability to concentrate on anything else.

Anxious individuals are prone to having clusters of worry-related information in their long-term memory. Hence, they are more likely to recall threatening events.

How anxiety impacts our decision-making

Interestingly, a study from the University of Pittsburgh discovered that anxiety also disengages neurons in the prefrontal cortex, which are linked to decision-making (Park et al., 2016). The scientists investigated two groups of rats (one anxiety-ridden and one relaxed). They completed a decision-making task, where logic was needed to receive a reward. The researchers found that anxiety suppresses the activity of neurons in the prefrontal cortex which are responsible for making choices on the basis of relevant rules. They concluded that the neural equation of fear and anxiety in the past has been too simple, and that anxiety disengages brain cells in a highly specialized manner. Therefore, reducing anxiety seems crucial for preventing a downward spiral of making poor decisions in the face of stress. Because this exacerbates anxiety leading to even more bad decisions. Lowering your anxiety level may therefore be a first step to perpetually make better life choices.

Humans and animals obviously needed fast and powerful emotional “fight-or-flight” responses to cope with physical danger. Yet nowadays we all lead relatively stable and safe lives. And it is often insanely difficult to find a rational reason for anxious feelings and worrying thoughts. There is panic, but no cave-dwelling warrior. There is suspense, but no action. And there is fear, but nothing visual to be afraid of. But, as we have seen, the mere fact that our safety might not be in acute danger, doesn’t make anxiety any less real or severe. However, knowing that anxious feelings are the result of imaginary stress makes them very frustrating to deal with. The question remains: What exactly in today’s world triggers anxiety?

Anxiety is the burden of what if’s …

As the number of available choices, upcoming changes and achievable successes continues to rise, the more autonomy and freedom we gain. This sounds (and is to a certain degree) absolutely amazing. But psychology research suggests there can be too much freedom and too much choice. Even back in 1844 the danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard described anxiety as a dizzying effect of freedom and paralyzing possibility. And indeed, the increasing overload and complexity of our environment is one of the biggest challenges in modern society.

… that may lead to decision paralysis

Studies show that being confronted with too many choices and options can induce decision paralysis. It describes that we find a large number of possibilities paralyzing rather than liberating. Evidence for this effect was shown in a study by Iyengar and Lepper (2000). Students had to evaluate either 6 or 30 varieties of gourmet chocolates. Afterwards, they were allowed to choose one of the chocolates as a payment for their participation. Surprisingly, the students with the small array were more satisfied with their chocolate choice than those with a large array. You probably wonder what these results show us in terms of anxiety. Well, the study of Iyengar and Lepper (2000) illustrates that the more options we have at hand, the easier it is to imagine all the things we have not chosen. Along with this theme, many of us utilize „What if…?”- questions to generate or maintain anxious states. We might be scared to choose or do the wrong thing (anticipated regret). Or we ruminate about all the other appealing choices we have missed or could have done better (post-decision regret). And as everything and everyone around us constantly seems to be improving, our standards of comparison go up. We put ourselves under an immense pressure. Of course we want to perform well and make the right life choices. At the same time, we are prone to blame ourselves for disappointing results: “With so many available opportunities, it is only myself to blame if I don’t achieve success.”

Too many choices and options can induce decision paralysis, in which we find a large number of possibilities paralyzing rather than liberating.

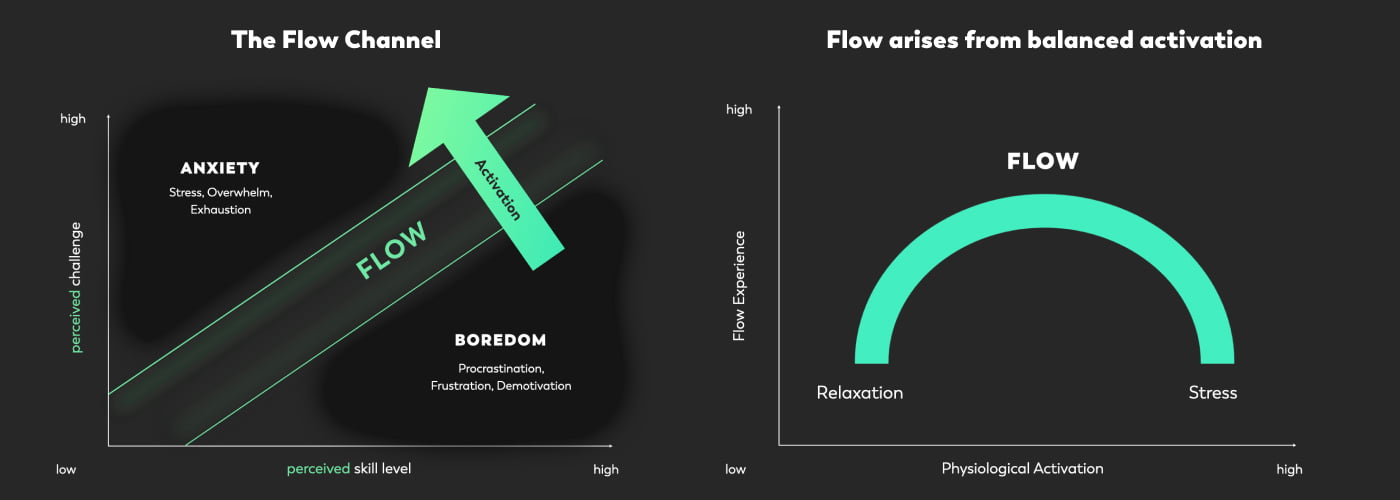

Anxiety and Flow

Surely, we cannot really change the world we are living in. However, we can gain a deeper understanding of the psychological variables that counteract anxiety. And you’ll certainly reap the benefits of learning how to cope more effectively with anxiety. Because this will pave the way for Flow! According to Flow theory, anxiety is considered to be the antithesis of Flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Flow correlates with the activation of the parasympathetic nervous system. This part of the autonomic nervous system counteracts the catabolic sympathetic activity that is responsible for stress and anxiety (Fullagar et al., 2013). And it also counteracts the activation of the sympathetic nervous system. You might already know that Flow requires a certain level of activation. We need to feel challenged, but not overwhelmed. In order to enter the Flow Channel – the sweet spot between boredom and anxiety – we have to step out of our comfort zone. If a task doesn’t challenge us, not only we don’t find Flow in the first place, but we also stop growing as a person.

The 4%-rule for more flow

A helpful guideline in this regard is the “4%-rule”: Your perceived challenge should be 4% above your perceived skill level. For Flow (so-called “autotelic”) personalities it is relatively easy to find a healthy dose of alertness and excitement, as they have learned to regulate themselves physically, mentally, and emotionally according to their needs. Hence, they are more capable of dealing with an imbalance between perceived challenges and abilities: Even if a task seems too demanding, they can handle negative feelings like overwhelm or anxiety by managing stress and being optimistic, thereby facilitating Flow. Lastly, the state of extreme arousal generated by anxiety correlates with ‘disintegrated’ attention rather than the focused attention during the Flow state. With these promising findings in mind, we have gathered a few mental tools for you. Use them to train your Flow skills while also counteracting anxious feelings!

4 science-based tips to overcome anxiety and find more flow

Tip #1: Control the Controllables

According to one of the leading anxiety experts David Barlow (2002), anxiety is greatly determined by a person’s perceived ability to control a potentially stressful event. Also the term “antiflow” has been defined as a demotivational state characterized by tedium and a lack of autonomy and control (Sorrentino et al., 2001). It is crucial to keep in mind that this refers to the individual’s perception of control. It is not necessarily about whether this feeling is accurate or not. Without a sense of control, we are more likely to expect negative outcomes and view the world as a chaotic and stressful place. If the uncontrollability of a situation makes you feel anxious, focus on the things that you CAN control. This can be your thoughts, your breath or the way you react to a certain situation. You can also check out our session “Driver’s Seat” in the Optimism training area to strengthen your control beliefs and confidence.

Tip #2: Let anxiety work for you

If we compare the relationship between flow and physiological activation in the model on the right with the Flow channel model on the left, we’ll realize the following: Flow (and therefore, performance) increases with physiological activation. However, if levels of arousal become too high, we become anxious and fall out of Flow. So performance decreases again.

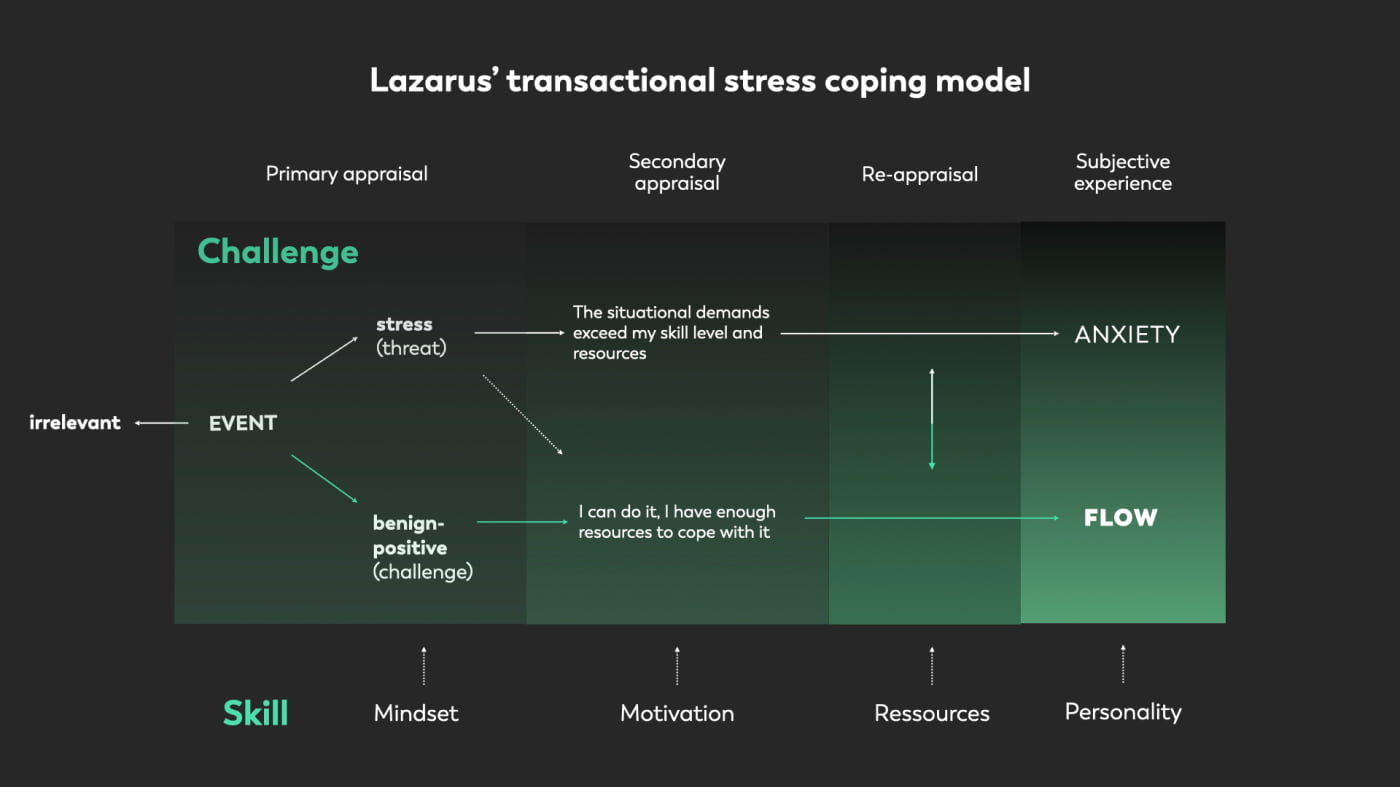

As strong anxiety won’t allow peak performance and flow, we need to learn how to cope with them and, at best, how we can ‘embrace’ anxious feelings. The groundwork for this is Lazarus’ transactional stress coping model: It illustrates that it is not an event or stimulus per se, but rather the cognitive evaluations, which decide whether you feel negative stress or not. In other words, the way we evaluate and assess a specific environmental event or situation determines our stress level.

Primary and secondary appraisals

Lazarus and Folkman (1984) differentiate between primary appraisal (an individuals’ subjective evaluation of a situation) and secondary appraisal (an individual’s evaluation of their ability to cope with a situation). For the psychology geeks out there: Primary appraisal can be further broken down into irrelevant, benign-positive and stress appraisals. A particular event is considered an irrelevant appraisal, if it doesn’t have any effect on our well-being. A benign-positive appraisal refers to a situation if it leads to positive beliefs, whereas a stress appraisal leads to beliefs that forecast harm and an experience of anxiety. Through cognitive reappraisal, you could either target the primary appraisal, reframing the situation as a positive, welcoming challenge. Or you target the secondary appraisal, reminding yourself of your resources and coping skills. Research suggests that reappraising anxious feelings as a harmless form of energy or excitement is a valid approach to cope with anxiety, especially under performance pressure. Besides, studies have shown that using statements of excitement helped improve singing, public speaking and math performance (Brooks, 2014). The next time you find yourself being anxious in the face of a challenge, use cognitive reappraisals like “This gives me energy and focus I need to perform” or “I am excited to do this”. We happily invite you to practice this technique in our sessions “Challenge Accepted” and “What if…” in the training area of Optimism.

Tip #3: Detect the rabbit hole of worry and anxiety

Anxious feelings are also often the result of dysfunctional thinking patterns, also called cognitive distortions. A few examples include an all-or-nothing thinking (“If I don’t get this promotion, I am worthless.”), fortune telling (“My presentation will be catastrophic.”), emotional reasoning (“I feel anxious, so the situation must be dangerous.”) or should-statements (“I should always be productive.”). If some of these sentences sound familiar to you, cognitive restructuring (e.g., changing the way you talk to yourself) might help you to consciously control and modify your negative ruminations. For instance, you can learn to replace the belief “I am a failure” with the thought “I may have failed in the past, but when I try my best, I often succeed“. If you are especially prone to negative thought spirals, have a go at our session “Unstuck” in the training area of Focus.

Tip #4: Breathe

An overreaction in the brain region of the amygdala plays a key role in exaggerated anxiety. Yet, according to research focusing your attention on your breath diminishes amygdala activity while also decreasing negative emotion experience (Goldin & Gross, 2010). Therefore, drawing attention to your breath whenever the world wants to take you in every other direction is not merely commonsense advice. Even scientists suggest that breathing techniques are suitable as a first line and supplemental treatment for stress, anxiety and depression (Jerath et al., 2015). For instance, you can try the so-called “physiological sigh”: Inhale two times through your nose and then exhale extensively through the mouth. Alternatively, go ahead and try out different breathing techniques in our sessions “Breather” or “Calm Winds” in the training area of Ease to calm down and to distract your mind from worrying thoughts.

Don’t let anxious feelings and worrying thoughts hold you back! Start your Flow training now and learn to regulate your emotions and physiological activation, so that you can stay calm, collected and optimistic – even in a world of paralyzing possibilities.

Start your training now